Levenshtein automata can be simple and fast

A few days ago somebody brought up an old blog post about Lucene’s fuzzy search. In this blog post Michael McCandless describes how they built Levenshtein automata based on the paper Fast String Correction with Levenshtein-Automata. This proved quite difficult:

At first he built a simple prototype, explicitly unioning the separate DFAs that allow for up to N insertions, deletions and substitutions. But, unfortunately, just building that DFA (let alone then intersecting it with the terms in the index), was too slow.

Fortunately, after some Googling, he discovered a paper, by Klaus Schulz and Stoyan Mihov (now famous among the Lucene/Solr committers!) detailing an efficient algorithm for building the Levenshtein Automaton from a given base term and max edit distance. All he had to do is code it up! It’s just software after all. Somehow, he roped Mark Miller, another Lucene/Solr committer, into helping him do this.

Unfortunately, the paper was nearly unintelligible! It’s 67 pages, filled with all sorts of equations, Greek symbols, definitions, propositions, lemmas, proofs. It uses scary concepts like Subsumption Triangles, along with beautiful yet still unintelligible diagrams. Really the paper may as well have been written in Latin.

Much coffee and beer was consumed, sometimes simultaneously. Many hours were spent on IRC, staying up all night, with Mark and Robert carrying on long conversations, which none of the rest of us could understand, trying desperately to decode the paper and turn it into Java code. Weeks went by like this and they actually had made some good initial progress, managing to loosely crack the paper to the point where they had a test implementation of the N=1 case, and it seemed to work. But generalizing that to the N=2 case was… daunting.

I tried to read the paper, but after a couple of minutes it was clear that he’s right: even understanding the paper would take a significant amount of time, let alone implementing the ideas in it. I thought there had to be a simpler way. After a bit of tinkering I had a working Levenshtein automaton in just a handful of lines of code with the same time complexity as the paper claims to have. Moreover it’s plenty fast in practice: for the N=1 and N=2 case which Lucene supports, stepping the automaton takes a small constant number of machine instructions. Another advantage is that unlike for the method in the paper there are no tables to generate, so it will happily work even for N=10 or N=100 (according to the paper the size of their tables grows very rapidly: 960, 25088, 692224 for N=2,3,4 which looks like >27N). I’ll also give an algorithm for converting the automaton to a DFA in linear time.

What’s a Levenshtein automaton good for anyway?

When you’re doing full text search your users may misspell the search terms. If there are no search results for the misspelled search term you may want to automatically correct the spelling and give search results for the corrected search term, like Google does with its “Did you mean X?”. If somebody searches for “bannana” you want to give them results for “banana”. The standard way of measuring similarity between two strings is the Levenshtein distance, which is the number of inserted, deleted and substituted letters. The Levenshtein distance between “bannana” and “banana” is 1 because there’s 1 ‘n’ inserted (or deleted, depending on which way around you view it). When a search query gives no results we could instead search for all queries with a Levenshtein distance of 1 to the query. So if somebody types “bannana” we would generate all words with Levenshtein distance 1 to it, and search for those. If that still doesn’t yield any results, we would generate all words with distance 2, and so forth. The problem is that the number of different search terms is huge. We can insert, delete and substitute any letter, so that’s “aanana”, “canana”, “danana”, etcetera, just for the first letter. This is especially impossible if you are using the full unicode alphabet. Another method, which is the method that Lucene used previously, is to simply scan the whole full text index for any word that is within a given Levenshtein distance to the query. This is very costly: the index could have millions of words in it so we don’t want to do a full search over the whole index.

A better approach is to exploit the structure of the index. It’s usually a trie, or a string B-tree, or even a sorted list of strings. A Levenshtein automaton can be used to efficiently eliminate whole parts of the index from the search. Suppose the index is represented as a trie:

This trie contains the words “woof”, “wood” and “banana”. When we search this trie for words within Levenshtein distance 1 of “bannana” the whole left branch is irrelevant. The search algorithm could find that out like this. We start at the root node, and go left via “w”. We continue searching because it’s possible that we will find “wannana” when we go further. We continue down to “o”, so now we are at node 2 with a prefix of “wo”. We can stop searching because no word starting with “wo” can be within Levenshtein distance of 1 of “bannana”. So we backtrack and continue down the right branch starting with “b”. This time we go all the way down to node 11 and find “banana”, which is a match. What have we gained? Instead of searching the entire trie we could prune some subtries from the search. In this example that’s not a big win, but in a real index we can have millions of words. The subtree under “wo” could be huge, and we don’t need to search any of it.

This is where Levenshtein automata come in. Given a word and a maximum edit distance we can contruct a Levenshtein automaton. We feed this automaton letters one by one, and then the automaton can tell us whether we need to continue searching or not. For this example we create a Levenshtein automaton for “banana” and N=1. We start at the root node and feed it “w”. Can that still match? The automaton says yes. We continue down and feed it “o”. Can that still match? The automaton says no, so we backtrack to the root. We also backtrack the automaton state! We feed that automaton “b” and ask whether it can still match? It says yes. We continue down the right path feeding it letters until we’ve arrived at node 11. Then we ask “does this match?”. The automaton says yes, and we’ve found our search result. Here’s the interface for a Levenshtein automaton in Python:

class LevenshteinAutomaton:

def __init__(self, string, n):

...

def start(self):

# returns the start state

...

def step(self, state, c):

# returns the next state given a state and a character

...

def is_match(self, state):

...

def can_match(self, state):

...We have a constructor that takes the query string and a max edit distance n. We have a method start that returns the start() start state. We have a method step(state, c) that returns the next state given a state and a character. We have is_match(state) that tells us whether a state is matching, and we have can_match(state) which tells us whether a state can become matching if we input more characters. can_match is what we will use to prune the search tree. Here’s an example:

automaton = LevenshteinAutomaton("bannana", 1)

state0 = automaton.start()

state1 = automaton.step(state0, 'w')

automaton.can_match(state1) # True, "w" can match "bannana" with distance 1

state2 = automaton.step(state1, 'o')

automaton.can_match(state2) # False, "wo" can't match "bannana" with distance 1To object oriented programmers this design may seem a bit strange. Your first inclination might be to represent the automaton state as an object, and do state.step(c) instead of automaton.step(state, c). You’ll see later that this design is the right one because we have both data for the whole automaton, such as “bannana” and 1, and data specific to a state. The classic object oriented design would force you to replicate the data for the whole automaton in each state, which is ugly.

The ML programmers in the audience will say “Of course, you’re using objects as a poor man’s modules, and classes as a poor man’s functors!”.

The O(length of string) version

If you look at the wikipedia page on Levenshtein distance you’ll find the standard dynamic programming algorithm. Given two strings A and B, we compute a matrix M[i,j] := levenshtein distance between A[0..i] and B[0..j]. It turns out that we can fill the matrix using the following computation:

M[0,j] = j

M[i,0] = i

M[i,j] = min(M[i-1,j] + 1, M[i,j-1] + 1, M[i-1,j-1] + cost)

where cost = 0 if A[i] == B[j], and cost = 1 otherwise.

If we fill the matrix row by row then we don’t need to store the full matrix. Once we’ve computed row i, we can throw away row i-1, so we only ever need to store a single row. This can be used to implement a Levenshtein automaton: as its state we use a single row of the Levenshtein matrix. Given a state (a row in the matrix) and a character c, we can compute the next state (the next row in the matrix) with the formulas above. We can implement is_match by looking at the last entry in the row, which contains the Levensthein distance between the query and the string of letters that was input to the automaton. If that number is less than n we have a match. Since the numbers in the row can never decrease by stepping, implementing the can_match method is easy too: we simply check if any number in the row is less than n. If there is such a number then we can still match if we input letters that match the query string, so that cost = 0. Here’s the code:

class LevenshteinAutomaton:

def __init__(self, string, n):

self.string = string

self.max_edits = n

def start(self):

return range(len(self.string)+1)

def step(self, state, c):

new_state = [state[0]+1]

for i in range(len(state)-1):

cost = 0 if self.string[i] == c else 1

new_state.append(min(new_state[i]+1, state[i]+cost, state[i+1]+1))

return new_state

def is_match(self, state):

return state[-1] <= self.max_edits

def can_match(self, state):

return min(state) <= self.max_editsThat’s all it takes to implement a Levenshtein automaton.

Converting to a DFA

Lucene builds a DFA out of the Levenshtein automaton. We don’t need to do that since we can search the index directly with the step() based automaton, but if we wanted to, can we convert to a DFA? A DFA has a finite number of states, but our automaton has an infinite number states. Each time we step the numbers in the row will increase. The thing is that many of those states are equivalent. For example if n = 2 then these states are all equivalent:

[3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

[500, 2, 1, 2, 500, 500, 500]

[3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3]

Once a number goes above n it doesn’t matter whether it’s 3, 5 or 500. It can never cause a match. So instead of increasing those numbers indefinitely we might as well keep them on 3. In the code we change the line

return new_stateto

return [min(x,self.max_edits+1) for x in new_state]Now the number of states is finite! We can recursively explore the automaton states while keeping track of states that we’ve already seen and not visiting them again. There’s one more thing we need however: the automaton needs to tell us which letters to try from a given state. We only need to try the letters that actually appear in the relevant positions in the query string. If the query string is “banana” we don’t need to try “x”, “y”, and “z” separately, since they all have the same result. Also, if an entry in the state is already 3, we don’t need to try the corresponding letter in the string, since it can never cause a match anyway. Here’s the code to compute the letters to try:

def transitions(self, state):

return set(c for (i,c) in enumerate(self.string) if state[i] <= self.max_edits) Now that we have this we can recursively enumerate all the states and store them in a DFA transition table:

counter = [0] # list is a hack for mutable lexical scoping

states = {}

transitions = []

matching = []

lev = LevenshteinAutomaton("woof", 1)

def explore(state):

key = tuple(state) # lists can't be hashed in Python so convert to a tuple

if key in states: return states[key]

i = counter[0]

counter[0] += 1

states[key] = i

if lev.is_match(state): matching.append(i)

for c in lev.transitions(state) | set(['*']):

newstate = lev.step(state, c)

j = explore(newstate)

transitions.append((i, j, c))

return i

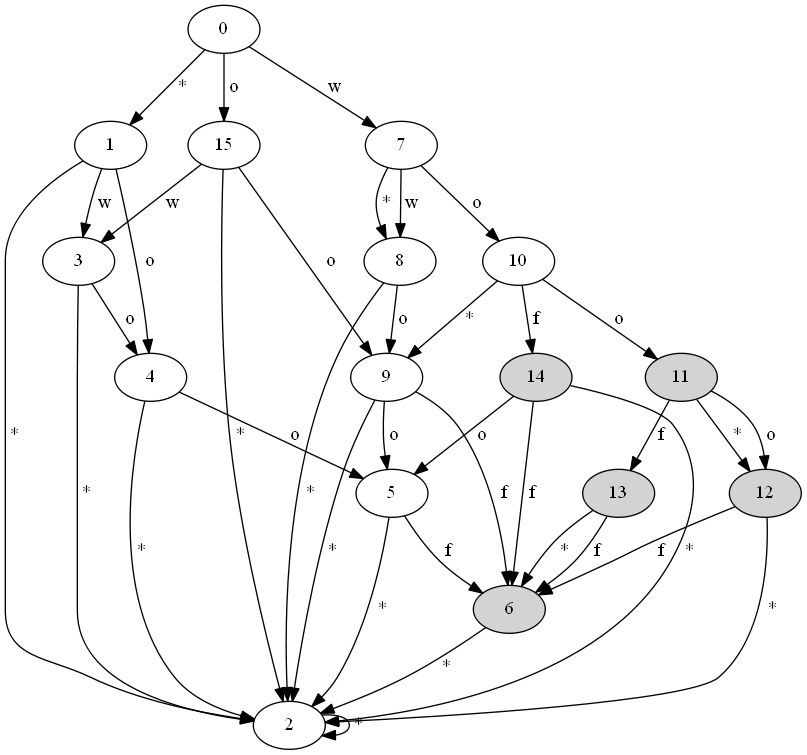

explore(lev.start())Here’s the resulting DFA for “woof” and n = 1:

The shaded nodes are the accepting states. In this case the DFA has the minimum possible number of states, but just like for the method in the paper this is not guaranteed to happen.

So how much time does it take to create this DFA? If there are k nodes in the DFA then we need to step O(k) times. Each step takes O(length of the query string) time, because we compute a matrix row of that size. So how many nodes are in the DFA? Let’s go back to what the Levenshtein matrix means. M[i,j] := levenshtein distance between A[0..i] and B[0..j]. The Levenshtein distance between a string of length i and a string of length j is at least |i - j|. So if we are in row number i, then only the entries i-n ... i+n are <= n. This is 2n + 1 entries. Let’s see what this means for Lucene’s use case, which only supports n = 1,2. For n = 1 each row has at maximum 3 entries which are <= 1 and for n = 2 each row has at maximum 5 entries which are <= 2. This means that for fixed n, there are only a constant number of entries in each row that we care about, so for fixed n the number of states in the DFA is linear in the size of the query string.

The O(max edit distance) version

So if we are building an automaton with n = 2 for a query string of size 1000, then each state is a matrix row of size 1001, but it will contain at most 5 entries which aren’t equal to 3! Why are we still computing the other 996 entries which are all equal to 3?! The standard solution to such a problem is to use a sparse vector. Instead of storing all entries, we only store the ones which are not equal to 3. Instead of this:

state = [3,3,3,3,3,3,3,3,3,3,3,2,1,2,3,3,3,3,3,3]

We store two small arrays:

values = [2,1,2]

indices = [11,12,13]

Remember that there are at most 2n + 1 entries not equal to n + 1, so these arrays will have a size that is independent of size of the string. Computing the step(state,c) becomes a bit more difficult with this representation, but not much more difficult:

class SparseLevenshteinAutomaton:

def __init__(self, string, n):

self.string = string

self.max_edits = n

def start(self):

return (range(self.max_edits+1), range(self.max_edits+1))

def step(self, (indices, values), c):

if indices and indices[0] == 0 and values[0] < self.max_edits:

new_indices = [0]

new_values = [values[0] + 1]

else:

new_indices = []

new_values = []

for j,i in enumerate(indices):

if i == len(self.string): break

cost = 0 if self.string[i] == c else 1

val = values[j] + cost

if new_indices and new_indices[-1] == i:

val = min(val, new_values[-1] + 1)

if j+1 < len(indices) and indices[j+1] == i+1:

val = min(val, values[j+1] + 1)

if val <= self.max_edits:

new_indices.append(i+1)

new_values.append(val)

return (new_indices, new_values)

def is_match(self, (indices, values)):

return bool(indices) and indices[-1] == len(self.string)

def can_match(self, (indices, values)):

return bool(indices)

def transitions(self, (indices, values)):

return set(self.string[i] for i in indices if i < len(self.string))Now each step takes O(max edit distance) time instead of O(length of string). So for Lucene which has max edit distance of 1 or 2, this is constant time. We can now build the DFA in linear time.

Conclusion

Do Levenshtein automata need to be difficult? We have an implementation with great worst case complexity in less than 40 lines of code, so I think the answer is no. There is lots that can be done to further optimize it, like rewrite it in a language that’s not as slow as Python, and perhaps write a specialized implementation for n=1,2. You could try more efficient representations. Using the fact that adjacent entries in a Levenshtein row differ by at most 1 we can represent the state as a bitvector. I’m not sure if that’s worth doing because it’s unlikely that stepping the automaton would be the bottleneck. A single disk seek is going to be much slower than any reasonable amount of stepping. That’s the real advantage of any Levenshtein automaton: we can avoid searching the entire index by intelligently pruning the search space.

I’ve put the code on github. It includes code for creating the graphviz drawings of the DFA.